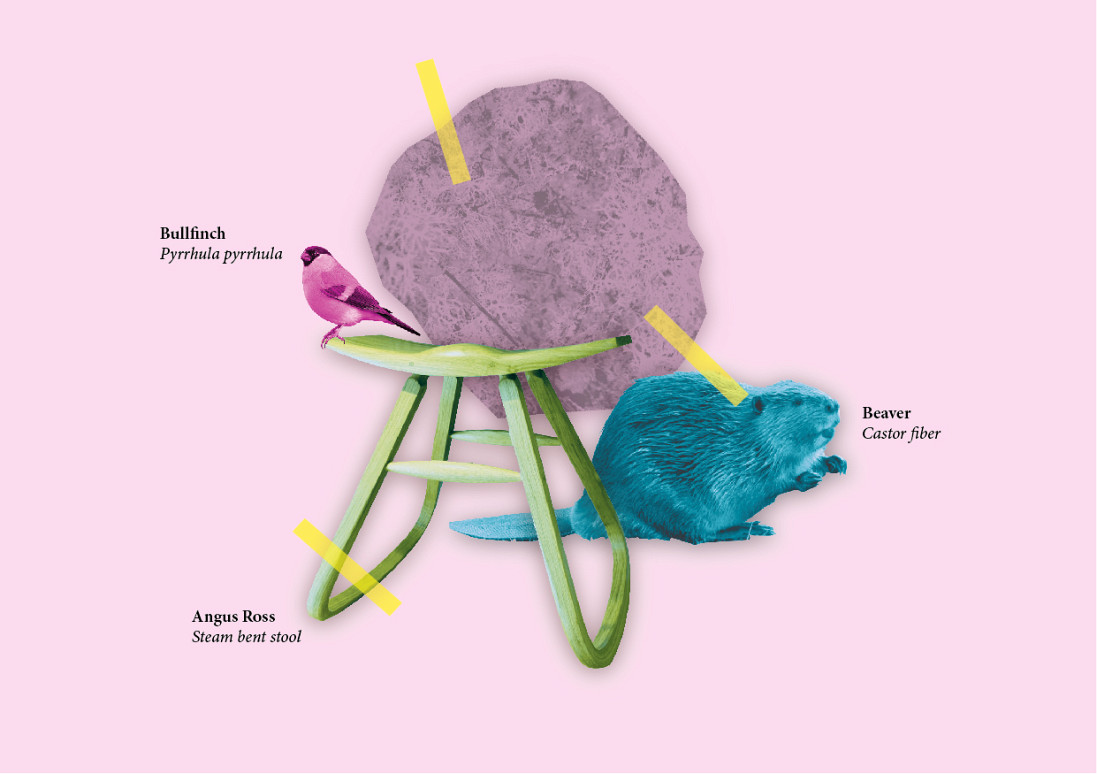

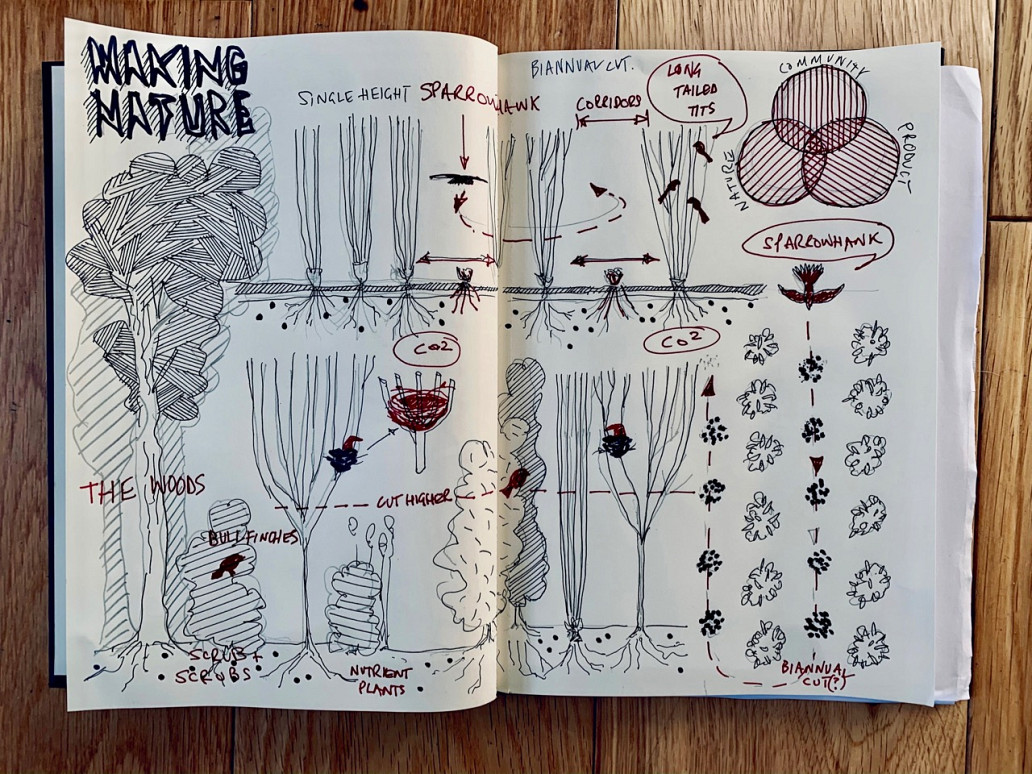

Our overarching research question seeks to understand if makers can directly support biodiversity, habitat restoration and ecosystem function through their making practices? (Gant, 2018)

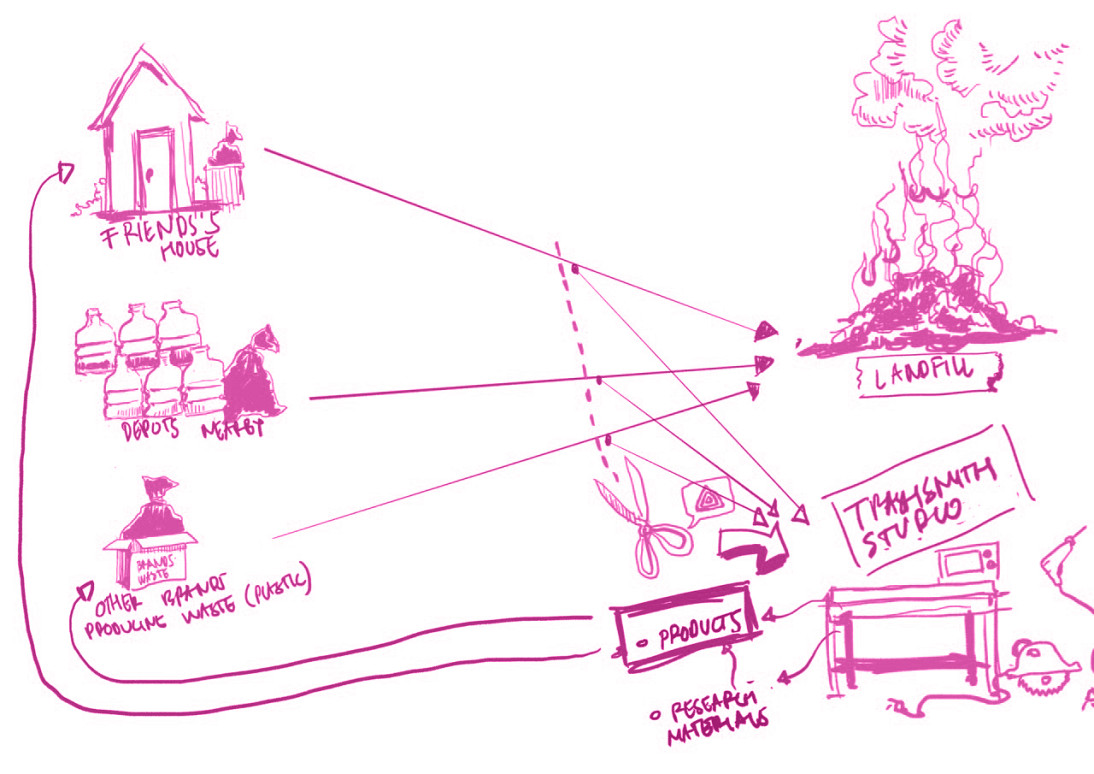

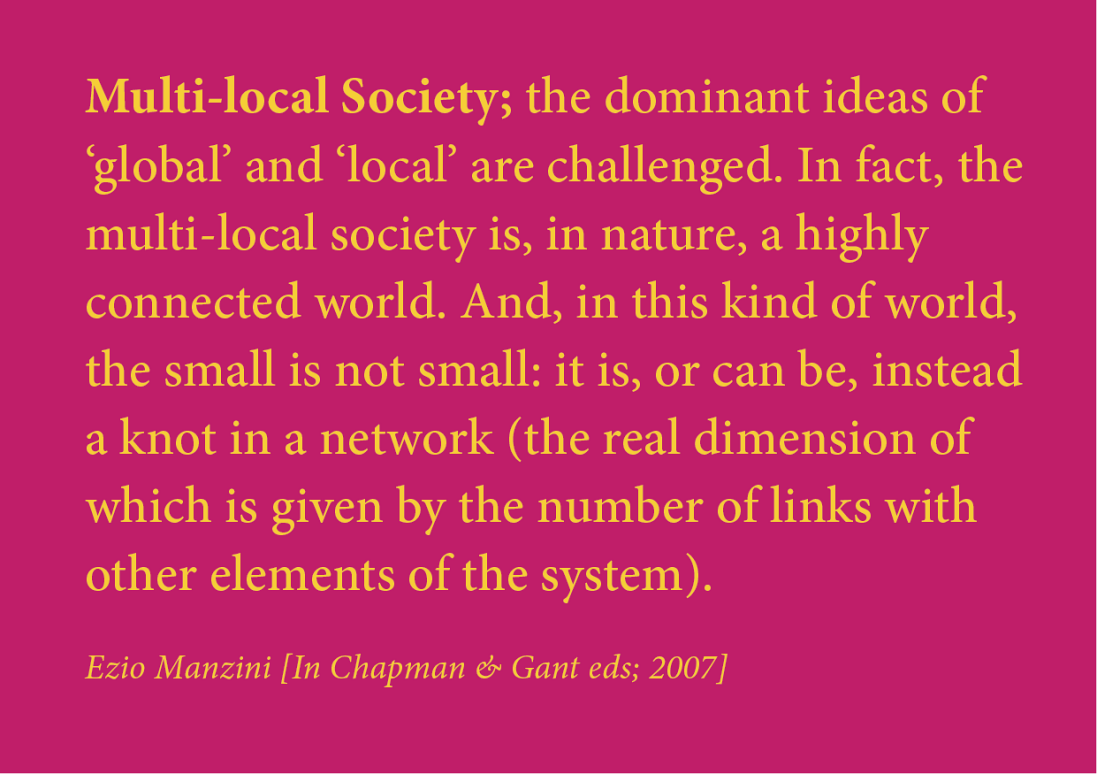

Implicit within notions of ’sustainability’ is the betterment of animal and plant species as one of the main underlying ambitions of ‘environmentalism’ and a key pillar of the 'circular economy' is the active regeneration of natural systems. However much of the response in design and making tends to focus on mitigating the indirect, negative impacts of human behaviour (for example the prevention of waste and negating pollution and reducing emissions).

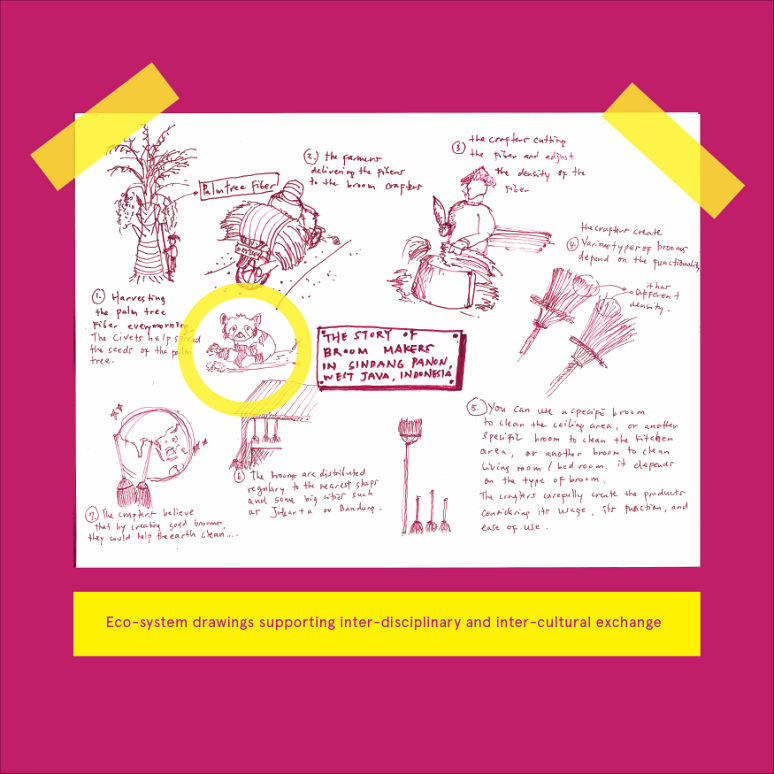

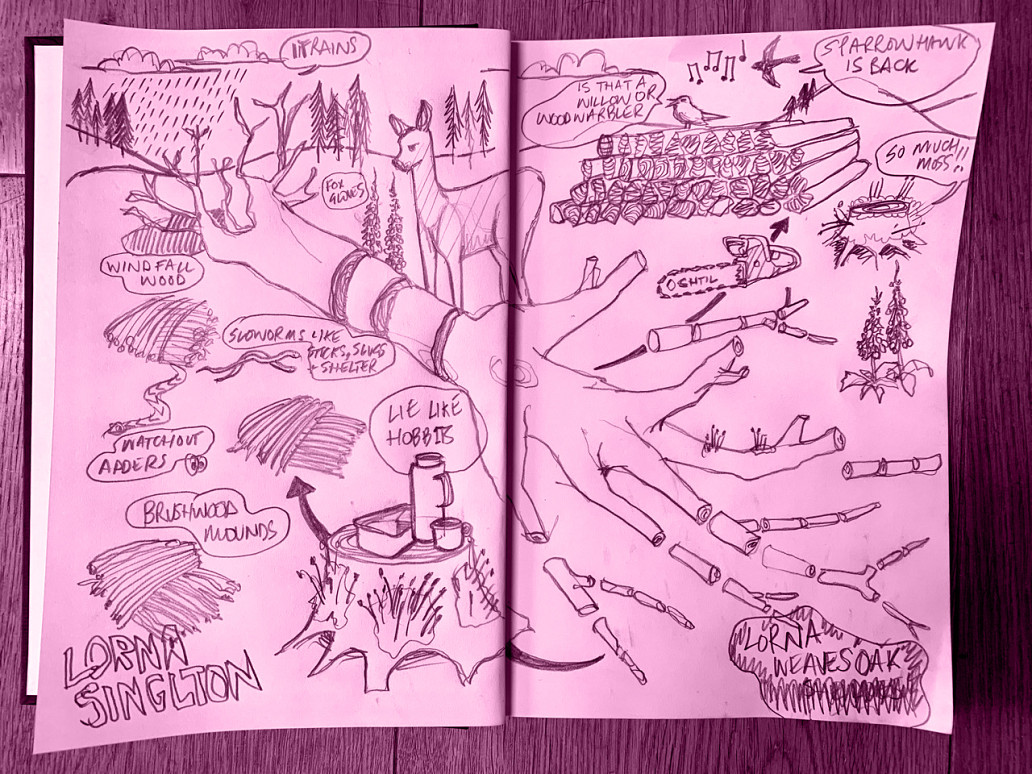

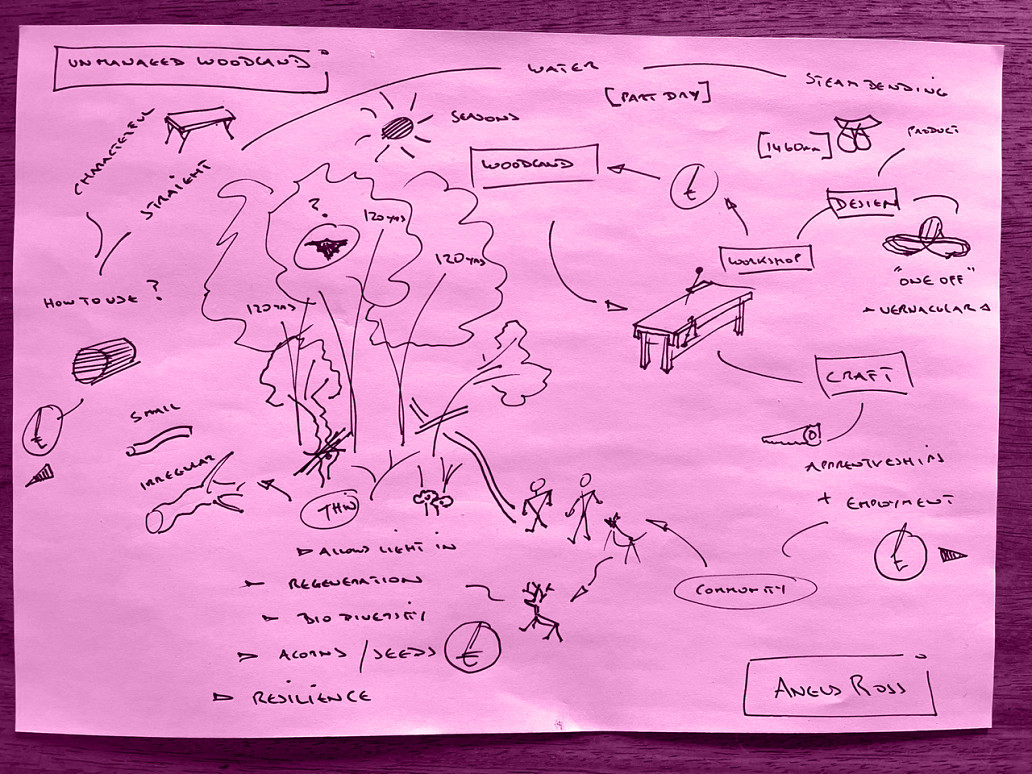

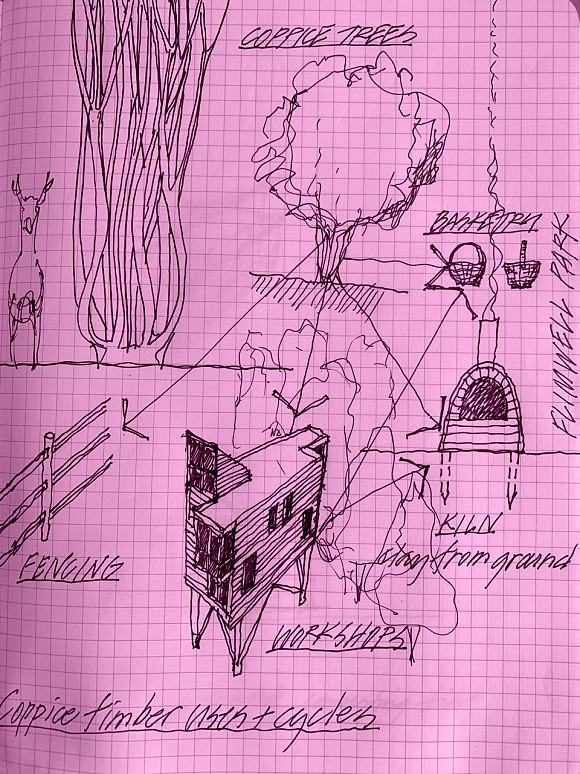

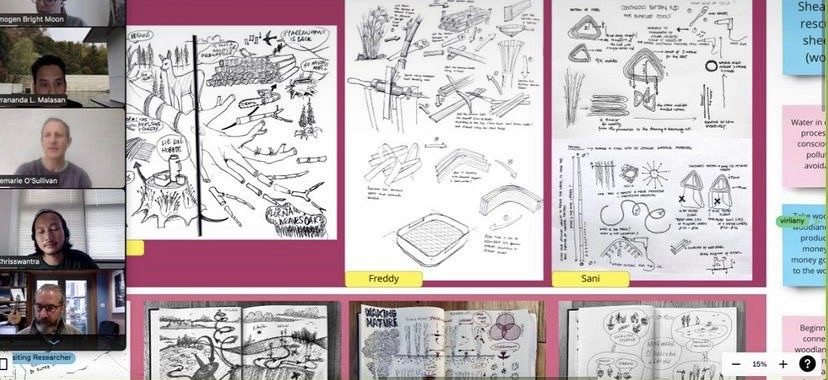

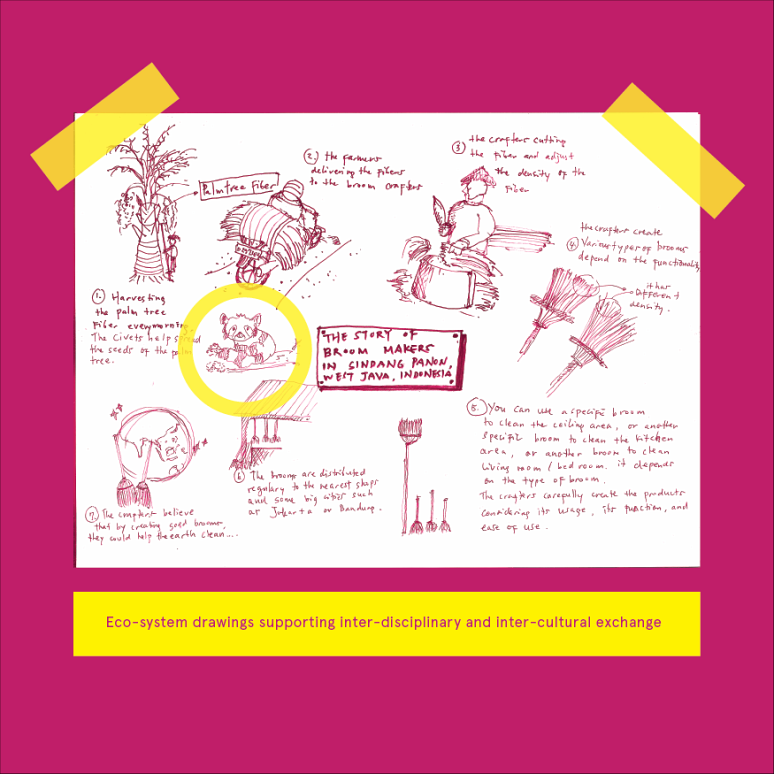

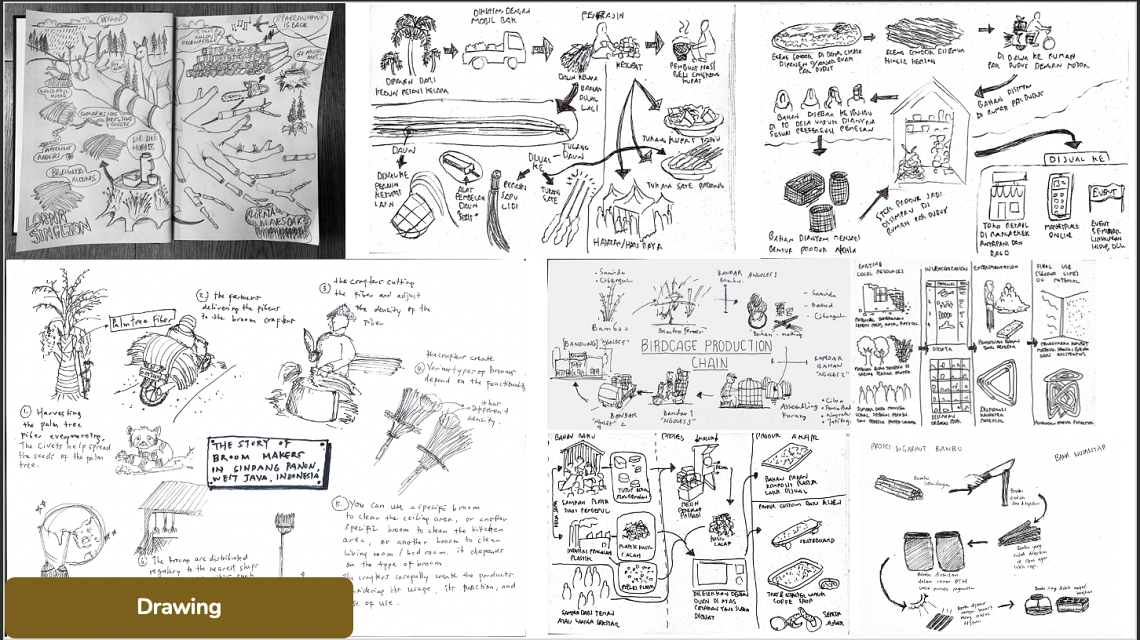

The Making Nature project and network engages with maker practitioners in the UK and Indonesia (initially) that may directly enhance biodiversity through their making activities and processes in ways that demonstrate more symbiotic relationships with nature and natural systems.

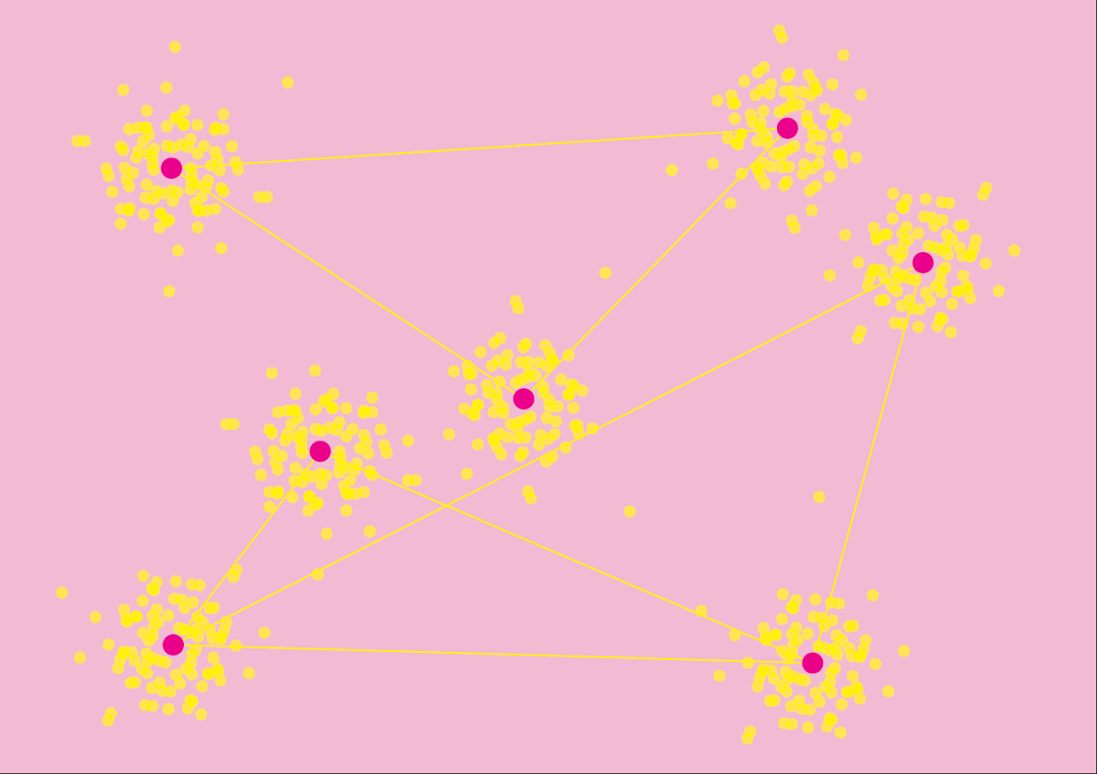

The map above navigates and plots some of our participants and this site content below features some initial findings from the study and associated publications feature further research details and foci.

The project has received funding and support by the British Council Crafting Futures Digital Collaborations programme - with further acknowledgements below.